Deaf people inhabit a rich sensory world where vision and touch are a primary means of spatial awareness and orientation. Many use sign language, a visual-kinetic mode of communication and maintain a strong cultural identity built around these sensibilities and shared life experiences. Our built environment, largely constructed by and for hearing individuals, presents a variety of surprising challenges to which deaf people have responded with a particular way of altering their surroundings to fit their unique ways-of-being. This approach is often referred to as DeafSpace.

When deaf people congregate the group customarily works together to rearrange furnishings into a “conversation circle” to allow clear sightlines so everyone can participate in the visual conversation. Gatherings often begin with participants adjusting window shades, lighting and seating to optimize conditions for visual communication that minimize eyestrain. Deaf homeowners often cut new openings in walls, place mirrors and lights in strategic locations to extend their sensory awareness and maintain visual connection between family members.

These practical acts of making a DeafSpace are long-held cultural traditions that, while never-before formally recognized, are the basic elements of an architectural expression unique to deaf experiences. The study of DeafSpace offers valuable insights about the interrelationship between the senses, the ways we construct the built environment and cultural identity from which society at large has much to learn.

The DeafSpace Project

In 2005 architect Hansel Bauman (hbhm architects) established the DeafSpace Project (DSP) in conjunction with the ASL Deaf Studies Department at Gallaudet University. Over the next five years, the DSP developed the DeafSpace Guidelines, a catalogue of over one hundred and fifty distinct DeafSpace architectural design elements that address the five major touch points between deaf experiences and the built environment: space and proximity, sensory reach, mobility and proximity, light and color, and finally acoustics. Common to all of these categories are the ideas of community building, visual language, the promotion of personal safety and well-being.

DeafSpace Concepts

1. Sensory Reach

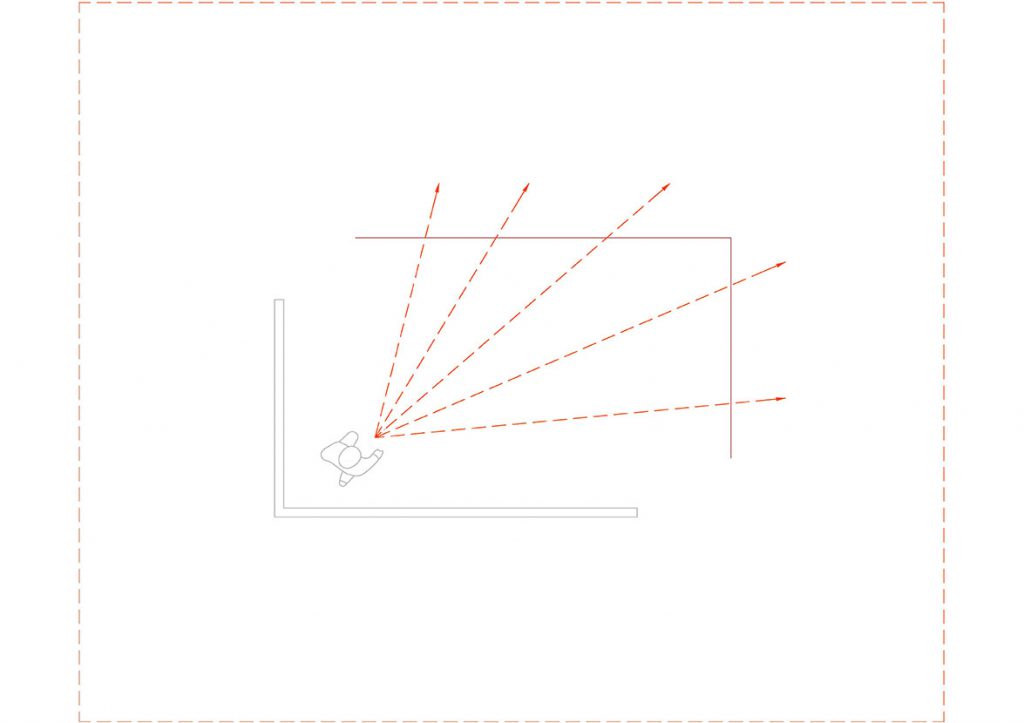

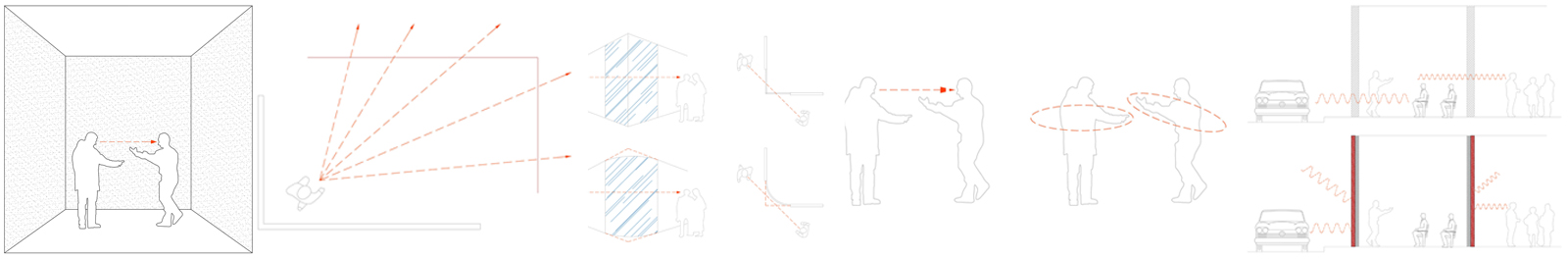

Spatial orientation and the awareness of activities within our surroundings are essential to maintaining a sense of well-being. Deaf people “read” the activities in their surroundings that may not be immediately apparent to many hearing people through an acute sensitivity of visual and tactile cues such as the movement of shadows, vibrations, or even the reading of subtle shifts in the expression/position of others around them. Many aspects of the built environment can be designed to facilitate spatial awareness “in 360 degrees” and facilitate orientation and wayfinding.

2. Space and proximity

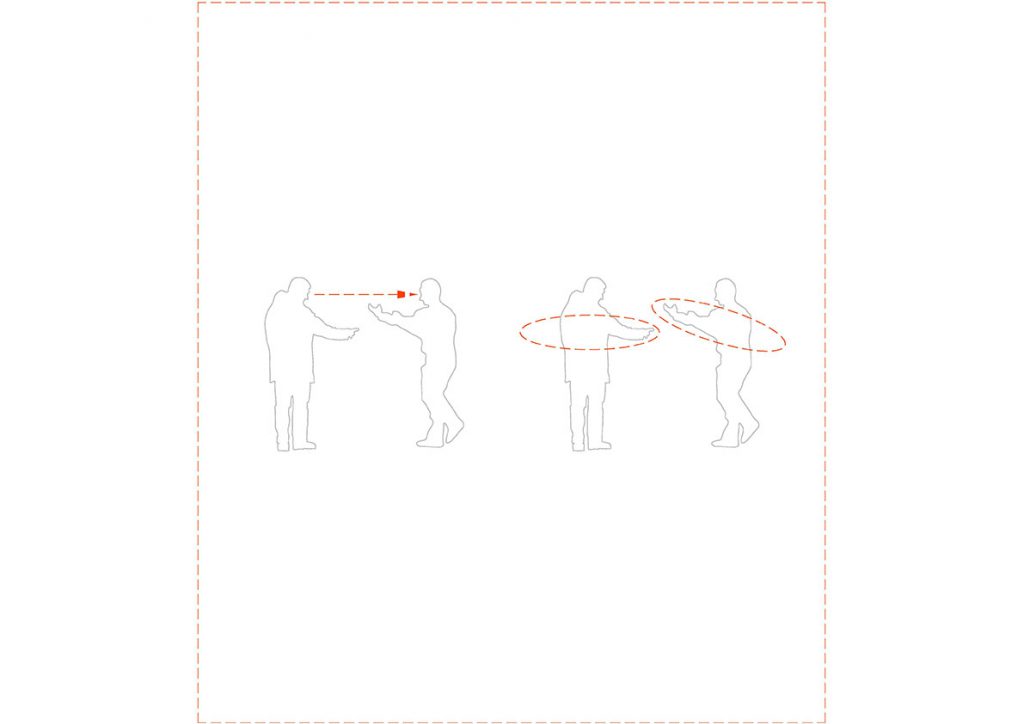

In order to maintain clear visual communication individuals stand at a distance where they can see facial expression and full dimension of the signer’s “signing space”. There space between two signers tends to be greater than that of a spoken conversation. As conversation groups grow in numbers the space between individuals increases to allow visual connection for all parties. This basic dimension of the space between people impacts the basic layout of furnishings and building spaces.

3. Mobility and proximity

While walking together in conversation signers will tend to maintain a wide distance for clear visual communication. The signers will also shift their gaze between the conversation and their surroundings scanning for hazards and maintaining proper direction. If one senses the slightest hazard they alert their companion, adjust and continue without interruption. The proper design of circulation and gathering spaces enable singers to move through space uninterrupted.

4. Light and color

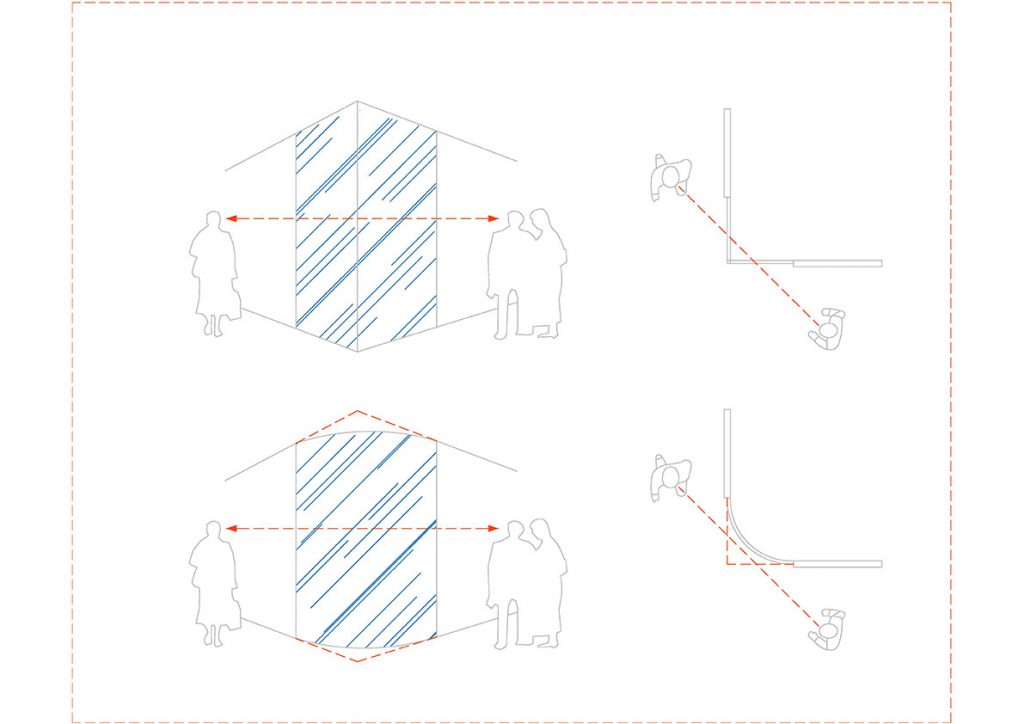

Poor lighting conditions such as glare, shadow patterns, backlighting interrupt visual communication and are major contributors to the causes of eye fatigue that can lead to a loss of concentration and even physical exhaustion. Proper Electric lighting and architectural elements used to control daylight can be configured to provide a soft, diffused light “attuned to deaf eyes”. Color can be used to contrast skin tone to highlight sign language and facilitate visual wayfinding.

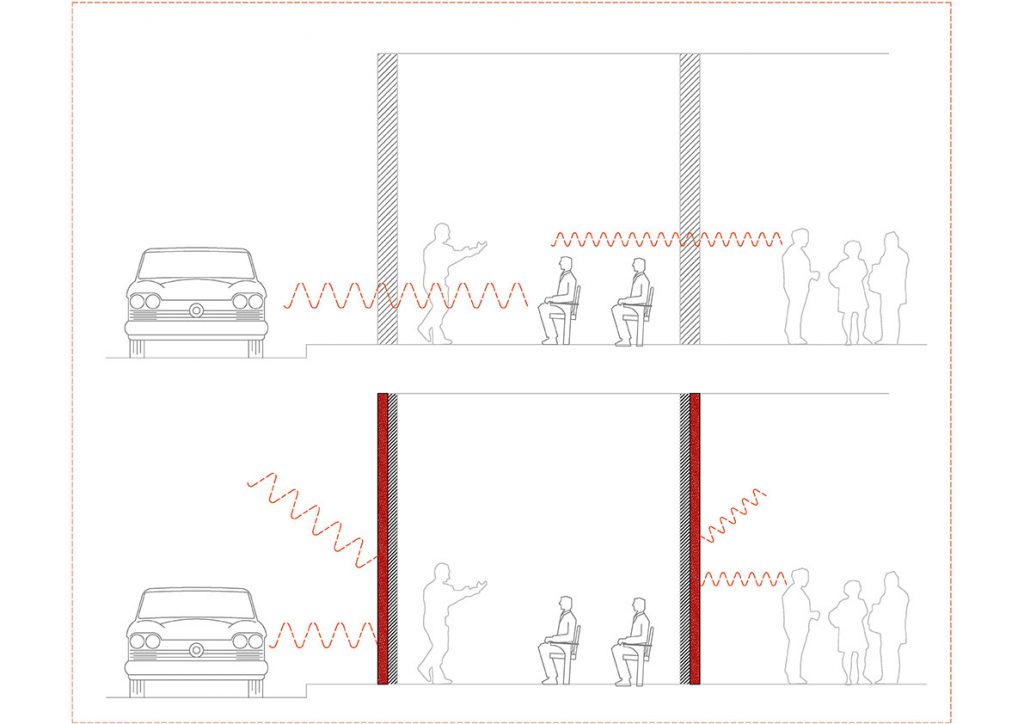

5. Acoustics

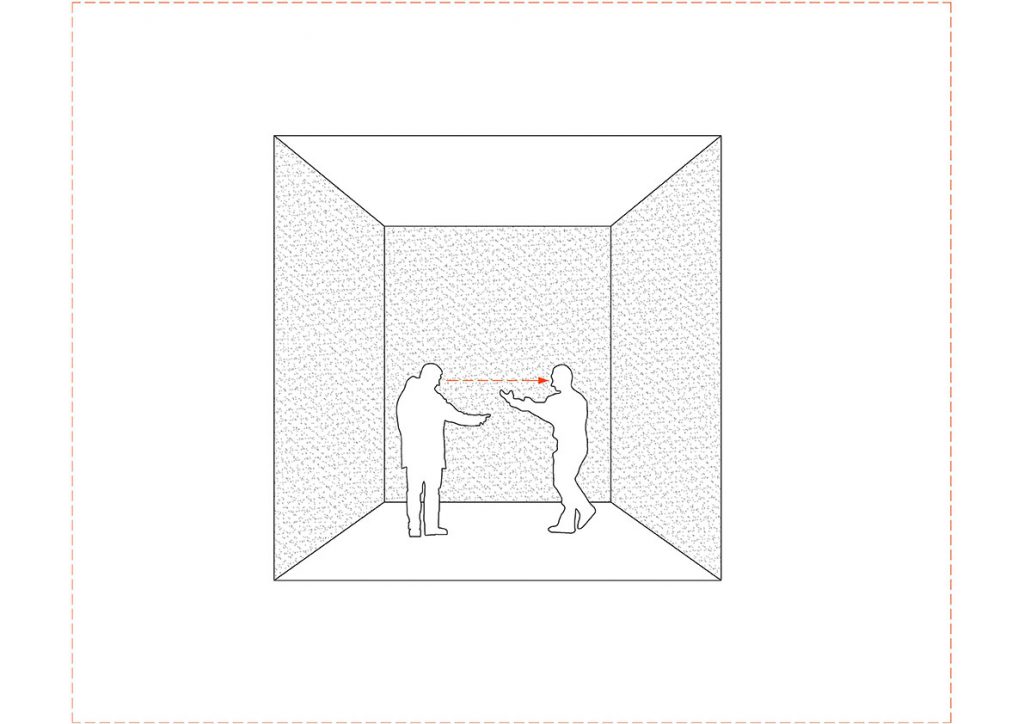

Deaf individuals experience many different kinds and degrees of hearing levels. Many use assistive devices such as hearing aids or cochlear implants to enhance sound. No matter the level of hearing, many deaf people do sense sound in a way that can be a major distraction, especially for individuals with assistive hearing devices. Reverberation caused by sound waves reflected by hard building surfaces can be especially distracting, even painful, for individuals using assistive devices. Spaces should be designed to reduce reverberation and other sources of background noise.

Images

© Dangermond Keane Architecture

http://www.gallaudet.edu/campus-design-and-planning/deafspace